Living Our Values When Facing Moral Dilemmas

March 17, 2025

This is part of a series of posts that looks at knowledge assets from New Pluralists' first four years.

When we talk about our work, we often hear variations of the same question: How do you draw moral lines when practicing pluralism? How can you—or should you—build relationships with people whom you perceive as working against the core values of pluralism?

Put another way: Is pluralism big enough to encompass anti-pluralistic ideas and actions — and should it be?

This is a difficult question, but an incredibly important one. The practice of pluralism demands affirming each other’s inherent dignity, widening the circle of belonging, finding strength in our differences, and moving beyond the ideas that one group’s gain is another’s loss. But where do we draw the line? Do we have to accept views or philosophies if they’re exclusionary or hateful? What if we widen the circle past its breaking point?

We continuously wrestle with these questions at New Pluralists, and we’ve concluded that pluralism is not moral relativism, or the idea that all values are equal. Pluralism does not mean that we have to be neutral, or that we have to partner with everyone.

But we also don’t believe there is a single set of values that everyone can agree on in all situations. And so we’ve developed an Ethics Practice to guide our approach to ethically and morally difficult situations.

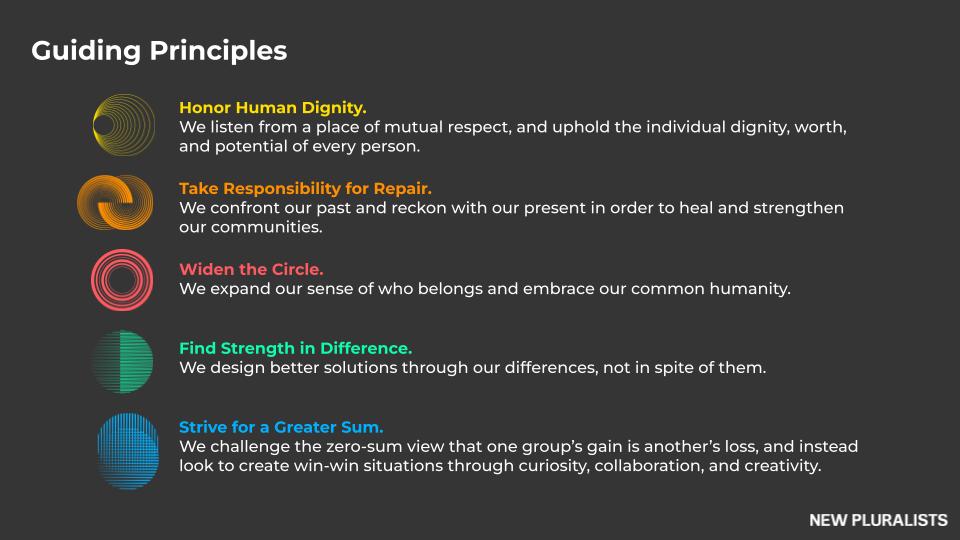

Our approach begins with our guiding principles:

Honor human dignity

Take responsibility for repair

Widen the circle

Find strength in difference

Strive for a greater sum

These principles offer a (relatively!) straightforward test for anyone we might consider working within our pluralistic mission: If they’re advancing these principles in good faith, there’s probably room for partnership. If they’re not, we likely need to scrutinize the potential for collaboration.

We can go a little further by defining what constitutes “good faith” — and what doesn’t.

Even if we disagree with an individual or organization’s views, philosophy, approaches, or policy prescriptions, there may still be an opportunity to engage so long as they:

Have a track record of honoring the fundamental equality of all people

Listen with openness and respond with integrity when made aware of our concerns

Show accountability

Conversely, we can identify behaviors that signal a person or organization is not practicing pluralism in good faith, and would not be a reliable partner in our work. These are:

Intent to harm

Undermining the equal rights of others

Undermining foundational democratic norms and practices

Refusal to reflect and improve

Taken together, a clear approach emerges: partnership is possible when partners act in good faith on the mission of pluralism.

Our Ethics Practice guides our approach to that difficult work, helping us answer the big questions and resolve the inherent tensions in connecting across diverse perspectives to reach a common goal.